- Home

- Christopher Hebert

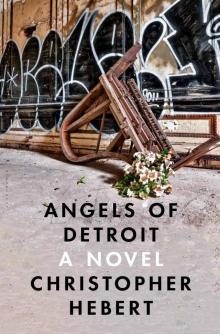

Angels of Detroit

Angels of Detroit Read online

For Margaret

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Boiling Season

Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus

(We hope for better things; it shall arise from the ashes)

Motto, official seal of the city of Detroit, adopted 1827

Contents

Spring

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Summer

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Fall

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Winter

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Spring

One

The car was a late-model Oldsmobile, the interior dank and musty, and the driver bore the distinctly sweet, rotting smell of overripe bananas. Lucius was his name. Thick dark hair sprouted from his knuckles in wild tufts. They were in southeastern Kansas, heading east as Patsy Cline quavered through a pair of broken speakers.

Dobbs hadn’t slept in days. He couldn’t put a firm number to it. The days whipped by like telephone poles. He feared he was losing the ability to see anything head-on. It was as if he and everything around him existed on separate planes, veering toward one another but never quite touching.

The noise of the highway made it sound as though Patsy were singing in the heart of a tornado.

After a couple of hours, they reached Lucius’s southbound exit, and Dobbs got out, shouldering his bag, moving on by foot.

* * *

At a truck stop in Topeka, he ordered coffee. Perched atop a pearlescent stool, he watched the pot empty its brown dregs into his cup. He imagined the coarse grit in the grooves of his teeth, the caffeine percolating through his veins.

There were only two other customers, each in his own remote booth. It was the hour for solitary travelers. The griddle was at rest, reflecting shimmery streaks of carbonized grease. A waitress hobbled from table to table with a magazine of straws clutched under her elbow.

“Your hair,” she said when she got to him. “Is it really that red?”

Dobbs caught his reflection in the mirror behind the counter. The color did seem unusually bright, the curls loose and wild. But his skin had the pallor of egg white. He was like a diseased tree, directing every last nutrient to its remaining leaves.

Every few minutes a thin, aproned boy came by and dropped a stack of dishes in the bus tub beside the counter. The dishes landed with an explosive charge buried at the base of Dobbs’s skull. Through the wall of hazy windows, he watched for trucks pulling in. He waited.

Other rides came and went. The drivers began to slip Dobbs’s mind the instant they pulled over, the moment they ducked to meet his eye through the open passenger window.

One night he found himself shivering, curled in the back of a pickup truck, sheltered within some sort of camper. Beneath the blankets lay a bed of cold steel. His eyes fluttered closed. He couldn’t seem to stop them.

In his dream, Dobbs was underwater. From somewhere up above, the light trickled down, like something solid falling. His lungs were strong. Rather than surface, he swam deeper and deeper. There was someone following him he couldn’t seem to shake.

And then the water was gone. Dobbs was sitting at a table in a cavern carpeted with sand. Exhausted from his swim, the man who’d been chasing him lowered himself heavily into the opposite chair. He smiled. They were like old friends meeting for a beer. But the man’s face bore only the faintest outline of something vaguely familiar. He spoke of women he’d known. His tone was nostalgic. He gestured lazily with his hands.

In his own hand, Dobbs held a wooden pepper mill, tall and slender, the curves perfectly contoured to his fist. The man winked, as if to beg Dobbs’s indulgence. Dobbs winked back. And then he raised the pepper mill. And then with a lunge, he smashed it back down, cracking the grinder against the man’s temple. Under the blow, the man swayed backward, but it was as though he were merely stretching. He sighed.

Dobbs struck him a second time, a third, a fourth. The blows left not a drop of blood, not a scratch, not a bruise. The man displayed no hard feelings, no discomfort, no indication of thinking things should be any different than they were.

Dobbs awoke with a shudder. The truck was slowing. They came to a stop on something loose and gravelly. Shards of light knifed through the door. Dobbs felt as though he were back underwater. But this time his lungs were spent.

He groped for a knob, a handle. There seemed to be no way out. Kicking aside the nest of blankets, he used his shoulder as a ram, but the wooden door of the camper absorbed him with indifference. Dobbs edged back and tried with his foot. But it was as if the light were pushing back.

Someone on the other side was yelling at him, but the cars slashing by warped the words. The lights formed blue and white and red spots on his eyelids.

Dobbs sat in the back of the cruiser as the cop fiddled with his computer, putting the finishing touches on the speeding ticket.

Up ahead, the truck and its makeshift camper pulled away from the shoulder of the highway, leaving him behind. Dobbs thought he felt something inside himself pull away with it.

On the other side of the partition, the cop cleared his throat.

Why don’t you have an ID? he wanted to know.

I don’t drive, Dobbs said.

Where are you coming from?

Phoenix.

What were you doing there?

A job.

Doing what?

It was temporary.

What was your address there?

I was only passing through.

A motel?

A house.

What was the address?

No one sent me any mail.

The cop had been looking down at the computer screen, occasionally keying something in as he talked. Now, for the first time, he lifted his face to look in the rearview mirror. His disembodied eyes hung there a moment, and Dobbs saw in them a weariness not unlike his own.

“Don’t you know hitchhiking is illegal?” the eyes said, raising one brow.

“I wasn’t hitching,” Dobbs said. “I was riding.”

“And you think it’s legal to be riding in the back of a pickup?”

“It is in Kansas.”

Which was true. And the cop knew it, too. Which was why he sighed.

These were the kinds of things a person had to keep track of. Walking the line required knowing exactly where the line was.

And so they rode in silence until they reached the border, Missouri on the other side.

“You’re someone else’s problem now,” the cop said, pulling over at the bank of the Kansas River.

For the next hour or so, Dobbs loitered through a light rain at a gas station just outside Kansas City.

“I’m trying to get to Detroit,” he said, as each new car pulled up to the pump.

No one would admit to being headed in his direction.

Of the next several days, Dobbs remembered only a gray-eyed man in a camouflage hat, gnawing on a pipe stem, saying, “Why don’t you get some sleep? You look like you could use some sleep.”

And Dobbs saying, “I’m fine, fine.�

��

Then minutes or maybe hours later, Dobbs was aware of the driver emerging from a fog of smoke to lean across the passenger seat and open the door. In Dobbs’s mind, there was a sudden clearing, like a flock of crows exploding from a treetop. He got out of the idling car, slowly testing the ground, one foot at a time. The car skipped away from the curb.

Dobbs was standing in front of the bus terminal. The sign at the gate said WELCOME TO DETROIT! The exclamation point was twice the size of the letters, as if whoever put it there were anticipating skepticism.

Dobbs didn’t remember having asked to be dropped off here. It was a strange choice. Had the driver thought the first thing he’d want to do as soon as he arrived was turn around and leave?

It was morning, early. The sky bleary. Dobbs was standing on a one-way street, but he turned to look in both directions. There were no other cars, no buses in the parking lot. There was no one out here but him. Down an embankment to his left ran the highway, but even it was mostly quiet.

He started walking, following the one-way arrows, heading south. He wasn’t far from downtown, but he was far enough that there was little to see—just a few sparse industrial buildings and a lot of fenced-off parking lots. He passed through a wide, nearly empty intersection, then another.

In a few minutes, he reached the river. The land along the shore was closed off from the road by a fence that appeared to stretch for miles, ending nearby at a cluster of high-rise apartment towers. Dobbs tossed his duffel bag over, then climbed the fence and dropped down on the other side.

Across the dense green water of the Detroit River was the dingy backlit skyline of Windsor, Ontario, the buildings all aglow. It was April, and every waitress in every diner across the plains had talked of little else but the arrival of spring. So far Dobbs wasn’t impressed. A chill had followed him all the way from the desert, never breaking. Now, standing on the windy shoreline, he fastened the button at the throat of his peacoat.

He’d spent the last week studying maps of the city. He knew the names of the streets, knew where they went. But the sights were unfamiliar, and the first ones he saw surprised him with their grandeur. Heading east, approaching downtown, he passed an old Gothic church with a towering green spire and limestone bricks that looked to have been chiseled by hand. Across the street, from a whole different century, rose a massive art deco building, all sharp lines and smooth stone block, arched windows trimmed in bands of bas-relief.

The city grew rapidly from there. Parking garages, towers, and offices of brick and glass. He reached a roundabout, circling a park. It was a peaceful, quiet place, ringed with birch and elm, paved in granite. The fountain hadn’t yet been switched on for the season, and at this hour, the shops and restaurants were still closed. But he could imagine people here, crowds.

He was in the heart of the city now. In the distance he caught a glimpse of the baseball stadium and the football field. Up the avenue to the north were the museums, the theaters, the opera house. Around the corner, the casino and restaurants. This was where the tourists came. This was where they stayed.

From his pocket, he removed a small square of paper.

Cross over the freeway.

The freeway marked the dividing line. Walking across the bridge, he could already feel the landmarks, the attractions, slipping away behind him. In the distance he saw a wall of graffiti bordering a compound of barren factory buildings clad in corrugated siding. The other part of the city, waiting to greet him. He kept walking, passing a cluster of crumbling brick industrial facades, vandalized, wrapped in rusted barbed wire. Then came a strip of storefronts, boarded up, tagged sill to sill in spray paint.

The note in his pocket said Go straight, quarter of a mile.

The avenue widened. On the opposite side was a group of warehouses, razor-wired parking lots stuffed with idling trucks. Faded block letters on cinderblock walls spelled out IMPORTS and EXPORTS, PRODUCE and POULTRY and MEAT.

The directions said Cross.

The sun was fully up now, but Dobbs was still chilled. At last he saw people: three men on a loading dock, gathered around cigarettes and steaming Styrofoam cups. A forklift beeped its way in the belly of the dark garage. They saw Dobbs, too, several sets of eyes following him as he went around the bend. Their expressions seemed to say where are you going? As if they knew something he didn’t.

But Dobbs already knew what lay ahead. Even so, he wasn’t quite ready for it, the moment the landscape changed again. It happened in an instant, as though a slide had been triggered before his eyes: a quick flash, and the warehouses vanished. The pavement gave way to weeds. The parking lots gave way to prairie. He’d simply turned a corner, and suddenly he found himself standing among barren fields framed by sidewalks. The city grid intact, but the city itself had disappeared. Empty. Whatever had once filled the emptiness was gone. Burned down, torn down, who knew?

Along with the maps, he’d gathered a few facts, a couple of which had stuck: a city of one hundred forty square miles, a third of it abandoned, the emptiness combined larger than the entire city of San Francisco. Boston. Manhattan. Almost two million inhabitants at the city’s height. Two-thirds of them now departed.

The directions said Keep going, but he couldn’t be sure where he was. The street signs had disappeared, too. There was the occasional house down one or another side street. Some of them had cars parked out front. Here and there among the weeds were the outlines of foundations. This must have been a residential neighborhood once. He tried to imagine what was missing: flower beds and latticed porches and picture windows framed in lace.

The directions stopped. He was supposed to have turned. But where? He went back, retracing his steps. What finally caught his eye was something just beyond a streetlight, tucked around a pair of crooked maples. From the side, as he approached, the place looked enormous, a dilapidated farmhouse shedding weathered gray clapboard. But as he got closer, he realized it was long but narrow, an old row house.

The place was all crazy angles. The front looked like a gingerbread castle, with a rounded tower honeycombed in hexagonal shingles. Every window on the front of the house was shaded by frilled, blue-and-white-striped aluminum canopies, which looked as though they’d been stolen from a boardwalk ice cream parlor. A rusty chain-link fence leaned in toward the house like a tightly cinched belt. Juniper shrubs that must once have been decorative now reached as high as the second floor, shielding the house completely from the empty corner lot next door. Between this house and the nearest neighbors were a couple of football fields’ worth of chest-high weeds.

There was no number on the house. None on the directions, either. But this was the place. It was exactly what they would choose.

The porch floorboards bent beneath him. The door was locked. Not so much as a wiggle in the knob. Reinforced and jimmy proof. There was not one dead bolt but two. The door was the only solid part of the entire house.

Downspout, the directions said. And so it was. They’d driven a nail through the gutter a few inches from the bottom. He slid off the key.

The inside of the house smelled of earth, of darkness. The windows had been papered over. The switches on the wall were dead. Once his eyes adjusted, he saw the place had been stripped bare. The hardware was gone from the doors and cabinets. Where before there’d been fixtures, there were now only holes.

Aside from securing the door and covering the windows, they’d done nothing else. The floor was crunchy with the shards of acorn shells. A couple of overturned soup cans had tumbled together into the corner. There wasn’t a single piece of furniture. There was no broom either, but he went outside and with his knife cut a needly branch from one of the overgrown shrubs. He swept the filth out the back door. Little by little fresh air trickled in.

In his dream, Dobbs was somewhere familiar, but he wasn’t sure where. He knew only that he’d been here before. The people were familiar too, but their features were vague. It was as if their heads had been carved in stone that

had washed away over time. There was something Dobbs was trying to tell them, something important he needed them to understand. They stood in a circle around him, as if awaiting instructions, but they seemed to be ignoring his every word. And so Dobbs went around the circle, one at a time, knocking them to the floor, beating them with his fists. Each patiently awaited his turn.

He woke up, leaning against the wall, his spine feeling as though it had been scraped with a dull blade. His watch said it was three o’clock in the morning. The only light in the house was a slight trickle coming from under the front door. In that trickle Dobbs noticed something that hadn’t been there before, a torn envelope folded over once. On the inside was that same familiar handwriting.

Three weeks. Be ready. Don’t fuck it up this time.

* * *

In the morning light, the paper-covered windows glowed like Chinese lanterns. Dobbs drank what little was left in his canteen. The house had no pipes, let alone a faucet.

It would be like camping, he told himself. Like being back again at the lake as a child, roughing it in the middle of nowhere. The scenery outside right now didn’t even look that different from what he remembered of the view from his grandfather’s cabin. Dobbs could recall the long drive north from St. Paul, past weedy logging roads and the sagging gates of ancient sawmills. Northern Minnesota. By the time Dobbs was a child, the forests all around his grandfather’s place had been reduced to pincushions. The quarries looked like meteor strikes. Along the backcountry highway, all that had remained were cinderblock shacks with rusted tin roofs and hand-painted signs offering diesel and bait.

His grandfather’s cabin had been off the grid, but Dobbs had loved every bit of it: lying on a cotton-stuffed sleeping bag on a slab of peeling plywood; peeing on trees and eating everything out of the same dented tin bowl; washing off in the turbid lake and fishing for dinner and building fires out of twigs and branches. Maybe nothing else lasted—not veins of iron or swaying pines—but the cabin itself had seemed as if nothing could touch it. After a week there, Dobbs had felt he could survive anything.

The Boiling Season

The Boiling Season Angels of Detroit

Angels of Detroit